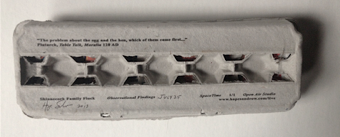

"...the problem about the egg and the hen, which of them came first, was dragged into our talk, a difficult problem which gives investigators much trouble. And Sulla my comrade said that with a small problem, as with a tool, we were rocking loose a great and heavy one, that of the creation of the world." Plutarch, Table Talk, Moralia 120 AD

A Hen lays an Egg after light-sensitive cells behind her eyes message her ovary to release an ovum into the egg yolk. Fertilized by sperm, coated by albumen, encased in shell as the egg travels through the oviduct. This creative process encompasses twenty-four hours; as the rotation of Earth on its axis.

Hope Sandrow spacetime

Observational Findings February 2007

(left) First Eggs in a nest created by Shinnecock’s mates, Matriarchs Cleo and Chloe

Padovana Chickens (aka Paduas aka Polands aka Polish) are members of an ancient breed of Fowls traced back to the Red Jungle Fowl and to feathered Avian dinosaurs 150 million years ago. Celebrated as great egg layers before the introduction of industrial farm practices favoring genetic modifications to increase egg production. A heritage breed, Padovana’s categorized now as “strictly for ornamental use”. Observational Findings documents the Flocks Hen’s and their chicks who emerged from eggshells they set on (minimum 21 days). Sandrow’s data (collected over fourteen years) proves “experts” (comments stated in blue on the following pages) incorrectly classifying them as “non-setters”. The first six chicks born at open air studio Shinnecock Hills were mothered by Padovana Gold Lace Hen Cleo, fathered by founder Padovana White Cockeral Shinnecock (2007).

They and their progeny, plus ten hens from Breeder Sylvia Babus and fifty-nine chicks (to prevent inbreeding), gave life to one hundred seventy-five chicks as of November 2021 (documentation follows). And (2018) eleven chicks hatched from Shinnecock Hen’s eggs placed in the controlled environment of an incubator (2018) because the extreme summer heat and humidity (optimal outdoor temperature between 60° and 80°; humidity 40 - 50%) killed chicks born under Hens. Fourteen chicks acquired from breeder (2019); thirty-one (2020); fourteen (2021): Gold Lace Hen Carina (born 2020) brought three chicks to life (2021).

Globally, 2021 was one of four (2020, 2019, 2016) warmest years on record continuing the planet’s long-term warming trend. Modern temperature records began in 1850.The world’s five warmest years all occurred since 2015, with nine of the 10 warmest years occurring since 2005, according to scientists from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). The Flock’s birth rate illustrates the impact of these temperature changes. In 2009, twenty-nine chicks emerged from eggshells set on by five hens; in 2010, seventeen (and one deceased) chicks brought to life from four hens. In 2011, unprecedented heat during breeding season resulted in only ten chicks emerging from eggshells set on by nine Hens. In March 2012, the Flock adapted to changes in climate: beginning breeding two months earlier in March rather than as usual in May. Their result was 39 chicks emerged from eggs set on by thirteen hens doubling the Flock’s numbers. In 2013, again adjusting to conditions on the ground (including the population that can be sustained on these grounds), seven chicks brought to life by three Hens setting on eggs, survived; four chicks by three hens in 2014; two chicks by one hen in 2015, six chicks by one hen in 2016. But in 2017 and 2018 none survived a few days after emerging from eggshells. In 2019, one chick was brought to life by one hen. (Note: for every birth from an eggshell, more then a hundred eggs not selected by Hens to be set on). In 2020, three chicks brought to life by three hens, survived; in 2021, three chicks were by one Hen. The Shinnecock Family currently (January 21 2022) consists of 65 Hens, 9 Roosters.

copyright © 2021 Hope Sandrow all rights reserved

(above) Observational Findings July 25 2013

12” x 3” x 3 1/2” Custom printed egg carton (Note 1), molted feather, newspaper clipping, a dozen eggs laid by Shinnecock Family Flock Hens, quote by Plutarch. quote by Sandrow

excerpt from Charles Darwin The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication 1868

Sandrow proposes a reconsideration of our relationship to nature and the natural world as we follow the unfolding story of Shinnecock and his descendants in her “living” art installation. As she and her muse Shinnecock illustrate the central premise of Michael Pollan’s seminal book The Botany of Desire “demonstrates how people and domesticated plants have formed a similarly reciprocal relationship”.

In any breed you'll get a few who will still set. In laying situations, those hens won't be kept alive, as they're supposed to be egg producers and when they go broody they lose out on 2-3 months of production with each clutch.

Barry Koffler, breeder of Shinnecock Flock founding Hens Cleo, Chloe, Clarissa, July 21, 2006

Note 1: Egg Cartons a subject of study in Response(mounted) 1989

An estimated 31,700 (as of October 2021) eggs laid by hens during the projects’ trajectory. Those not set on by Hen’s for breeding were consumed by Sandrow and Skogsbergh, shared with family, friends, colleagues, neighbors, Shinnecock Indian Nation Food Pantry, The Retreat.